As the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was managed by Soviet authorities in Moscow, the government of Ukraine did not receive prompt information on the accident, and hence, on the morning of the 26 April, the fifty-thousand inhabitants of the City of Pripyat went about their business as normal, unaware of the catastrophic events taking place just five kilometres away. Within a few hours of the explosion, dozens of people fell ill, later reporting severe headaches, a metallic taste in their mouths, along with uncontrollable fits of coughing and vomiting. It was not until the morning of 27 April, some thirty-six hours after the initial explosion, that the decision was made by a joint Ukrainian/Soviet commission to evacuate the city. Residents were initially informed by the authorities that the evacuation would be temporary and to take only essential items. On 28 April the area of evacuation was extended to a ten kilometre radius of the Chernobyl plant. Ten days later this area was extended to a radius of thirty kilometres and has remained in place ever since. As a result the inhabitants of Pripyat never returned to their homes, leaving many personal belongings behind.

Palace of Culture

Palace of Culture

The people carriers parked opposite the Palace of Culture, the former civic centre of the city and after further briefing on safety precautions (it’s best to avoid moss as this holds radioactive particles like a sponge and can emit a radioactive dose of 25,000 µSv/h) we were allowed to wander around the immediate vicinity, including the elementary and high schools, the now famous Azure swimming, the equally famous Pripyat amusement park, and the Palace of Culture itself. Out-of-bounds areas were indicated with red flags.

Wandering around the central precinct of Pripyat, a post-apocalyptic relic of the twentieth century’s most notorious industrial accident, was an emotional experience. Excitement and awe at being physically in an area which for so many years had been closed off to human access combined with a deep sense of tragedy, and what I imagined was an echo of the fear felt by the thousands of souls that had fled in what I can only imagine were horrific circumstances. At around 14:00 on 27 April the evacuation of the city began but took several hours to complete as the citizens of Pripyat had to be mustered at various locations around the city, forming orderly queues for buses that would take them away from immediate danger.

Strikingly, within the assembly hall of the elementary school, several hundred gas masks still lay in a pile upon the floor, their lifeless eyes opened wide as though in shock at the unfolding disaster. Part of me suspected that this disturbing scene had been staged for the benefit of tourists like myself, but it felt genuine, the masks dusty and colourless, untouched for decades. They would have offered little protection against radionuclide from the burning reactor, and perhaps in the rush to evacuate the children from the school a decision was made to leave them behind.

The Pripyat Amusement Park, comprising four rides: a twenty-six meter ferris wheel, bumper cars, swing boats and a paratrooper ride, was scheduled to open on 1 May 1986 as part of the Soviet May Day celebrations. Some accounts claim that the park was briefly opened during the day on 27 April, possibly in an attempt to distract the residents of the city from the rumours that were wildly circulating about just what was happening five kilometres away at the Chernobyl reactor, but images I have seen claiming to be of the ferris wheel in operation show a different supporting structure to the Pripyat wheel. The park has become a cultural icon of the Chernobyl disaster and has appeared in the video game Call of Duty 4 and the film Chernobyl Diaries. A significant part of the plot of the 2013 Bruce Willis film A Good Day to Die Hard is set in Pripyat.

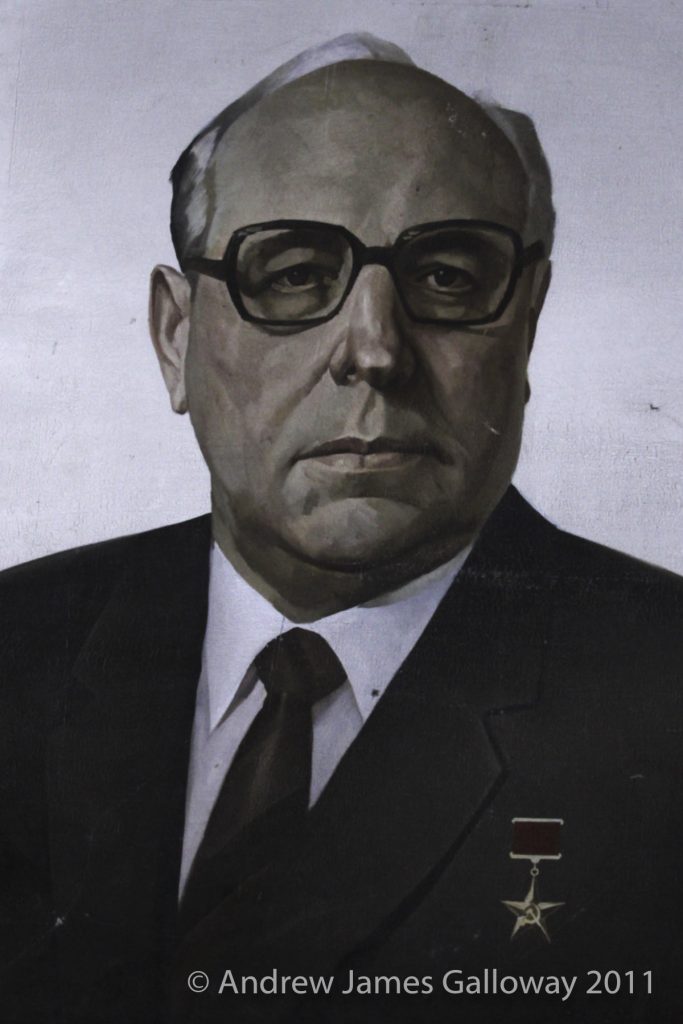

After an hour or so of exploring amongst the ruins of Pripyat, seemingly more concerned about keeping to the timing of the tour than of any risk of exposure to radiation, our tour guides ushered us into the people carriers and we were ferried away to the main reactor complex. After a relaxed lunch at the Dining Chernobyl Nbr 19, a former canteen for the power plant workers we were invited to visit the statue of Prometheus, which stands be a memorial to the power plant workers who were killed in the disaster.

Sarcophagus

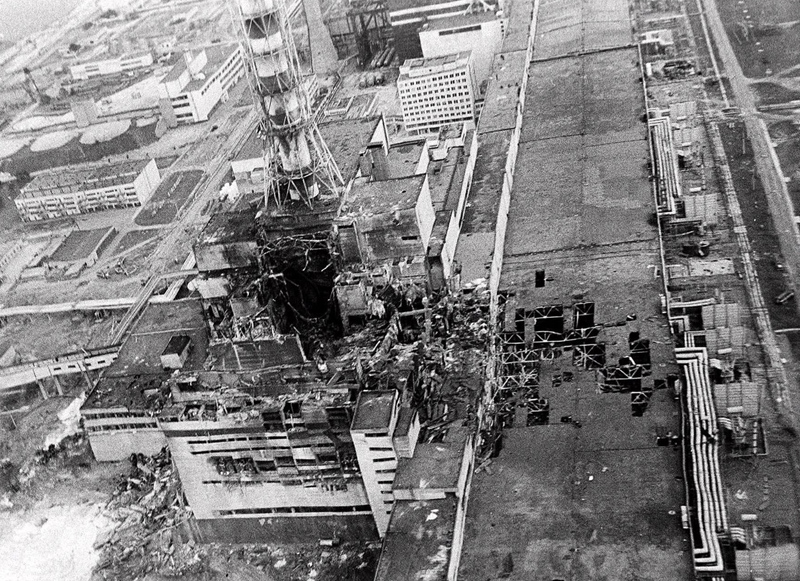

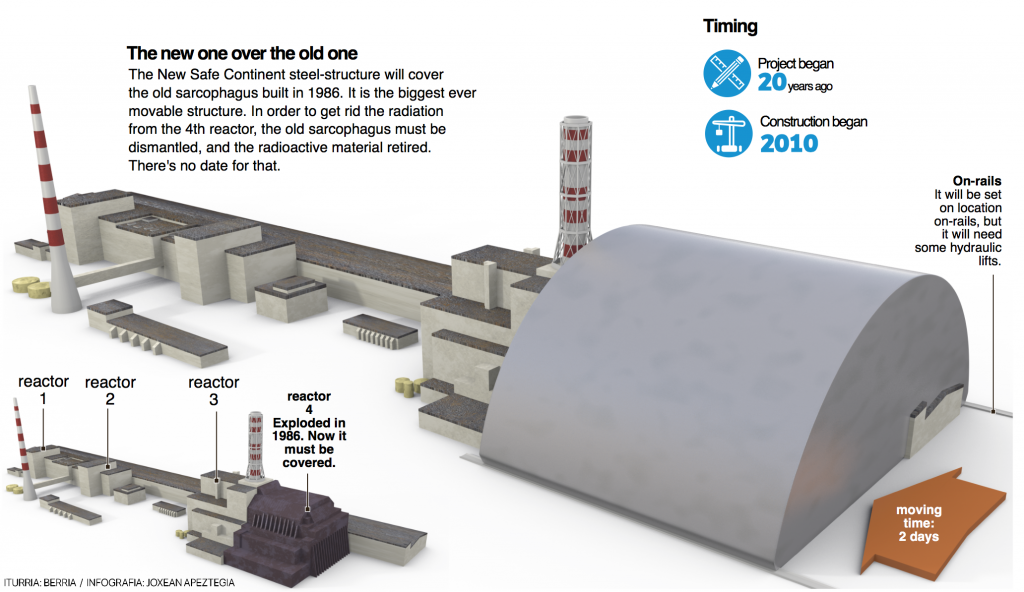

The final stop on the tour was the Sarkofag Chornobylʹsʹkoyi Aes, a viewing point approximately three hundred metres from the sarcophagus covering the remains of reactor 4. This was as close as we were permitted, and certainly as close as we wished, to get to the sight of the 1986 explosion. Construction of the first sarcophagus began in May 1986 and took two hundred days to complete. The sarcophagus locked in 200 tonnes of radioactive corium, 30 tonnes of highly contaminated dust and 16 tonnes of uranium and plutonium left behind after the explosion. In 1996 concerns about the structural integrity of the sarcophagus were raised, specifically corrosion of the supporting steel structure by contaminated rain water, and a decision was taken to replace it with a New Safe Confinement structure. With the help of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, a conservation programme was completed in 1998, which included securing the roof beams from collapse. The New Safe Confinement structure was completed and moved into place in 2016.

Environmental Effects

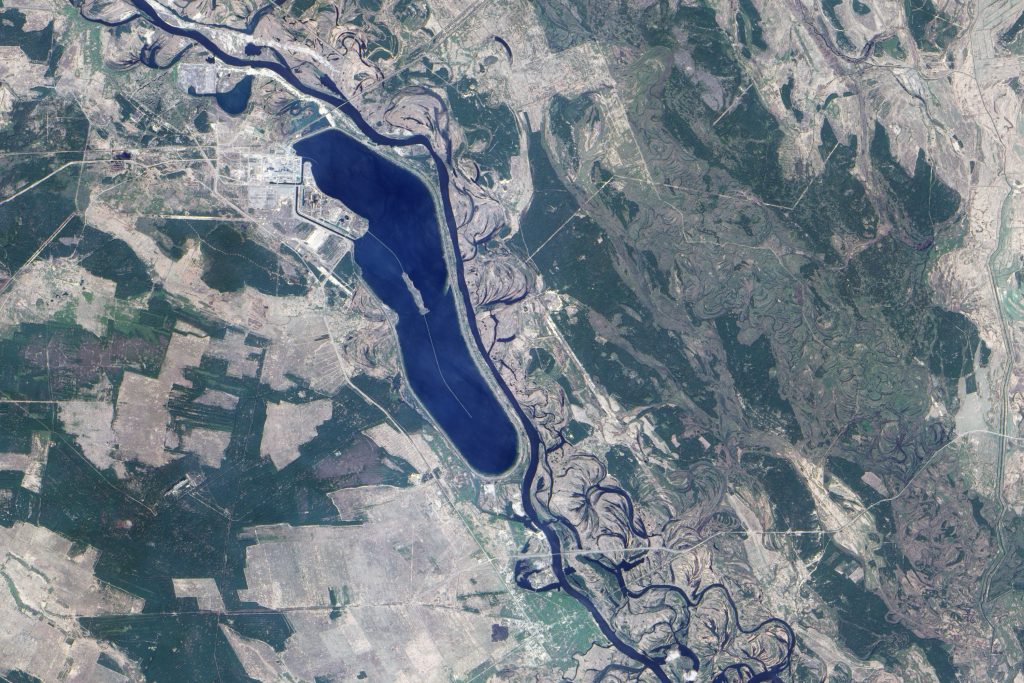

On the drive back to Kiev we stopped at an iron frame road bridge spanning a water channel into the cooling pond where we fed enormous cat fish with hunks of bread. These remarkable fish are Wels Catfish (Silurus glanis). Despite much speculation their gigantic size is not a result of radioactive mutation, rather they have taken advantage of the sparsity of the human population to fully take advantage of their environment. The BBC reported in 2016 that wildlife in the Chernobyl exclusion zone is thriving. This is not to say that the effects of high levels of radiation immediately following the explosion were not devastating. During the first two years following the reactor fire many trees within an area of coniferous forest covering between 4 and 5 sq km died. The dying needles turned rusty red, earning the region the name Red Forest. During this period, in the most contaminated areas many soil invertebrates were killed, and the small mammal population plummeted. Thirty years on radiation levels within many areas of the exclusion zone have dropped significantly. Although, like the Wels Catfish, many species have exploited the absence of the natural world’s most devastating predator, homo sapiens, a study undertaken in 2009 by Anders Møller and Timothy Mousseau suggested there was a serious impact on insect abundance even in areas of the exclusion zone where radiation levels are now extremely low. Research into the long term effects of the Chernobyl disaster continues.

The Future of Nuclear Power

The UK currently has 15 nuclear reactors with a total generating capacity of 10 gigawatts of electricity (GWe), operated by EDF Energy. These stations generate around a fifth of the UK’s electricity, yet all but one is scheduled to be retired by 2030. With the exception of the Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) at Sizewell B, the UK power plants are second generation Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors, considered to be considerably safer than the RBMK graphite-moderated reactors of the Chernobyl plant. Although many modifications were made to the RBMK reactor design following the Chernobyl accident, as of December 2017 there were still eleven RBMK reactors, and four small EGP-6 graphite moderated light water reactors operating in Russia.

The current UK government has expressed a desire to expand nuclear power generation over the next ten years, however, these aspirations were thrown into doubt in November 2018 following the decision by Toshiba to withdraw from the proposed NuGen PWR construction project in Cumbria. In January 2019 the Hitachi owned subsidiary Horizon Nuclear Power announced its decision to halt production of the Wylfa Newydd Advanced Boiling Water Reactor power station located on the island of Anglesey, North Wales. Both companies sited an inability to attract investors as the primary reasons for withdrawal from the projects. The only new nuclear power station project currently underway in the UK is the EDF Hinkley Point C PWR plant, scheduled for completion by 2025 at a cost of £20.5 Billion.