Broad Stand, as the notorious flight of granite steps on the eastern flank of Scafell is known, is a death trap. A quick look at the Wasdale Mountain Rescue Team website will confirm the number of incidents that have taken place at this accident black spot. These range in seriousness from a family of four and their dog who had become stuck on the ledge half way up the crag, to a fell walker found dead beneath East Buttress on 2 July 2017.

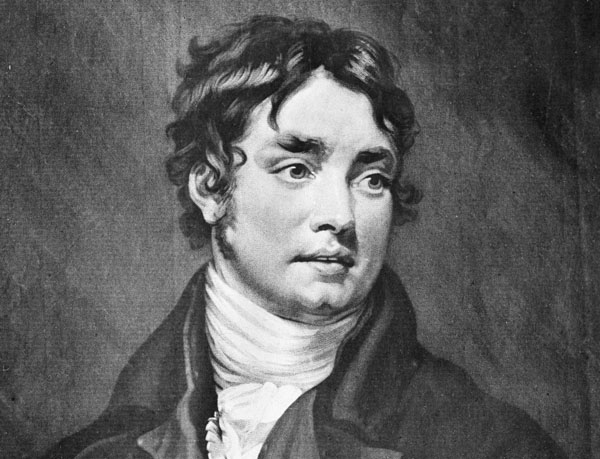

Not recorded on the Wasdale Mountain Rescue Team website is the descent of Broad Stand made by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge on 5 August 1802. Coleridge set out from Greta Hall, his home in Keswick, carrying little more than a change of under garments and some simple writing materials, bound up in a “natty green oil-skin” held together in a net knapsack. Through the Newlands Valley he climbed by the waterfall of Moss Force, then descended into Buttermere and took tea at the Inn by the lake. From Floutern Tarn he descended into Ennerdale and spent the night at the home of John Ponsonby at Long Moor.

Coleridge departed Long Moor after tea and arrived late at St. Bees. He was unable to find suitable accommodation and was forced to spend the night in his clothes at a “miserable pot-house”. He lingered at St. Bees a day then walked on to Egremont, from where via Gosforth he followed the River Irk upstream to reach Nether Wasdale.

Having spent the night at Wasdale Head, Coleridge climbed in the fresh morning light to Burnmoor Tarn, then followed the torrent of Hardrigg Gill to the rocky summit of Scafell itself, where on a natural table of granite he took from his knapsack the paper and pens he had placed there upon leaving Greta Hall and began to compose the letter to his friend Sara Hutchinson from which the details of this account come.

By three o’clock in the afternoon the wind had begun to gather around the summit such that Coleridge sought his descent from the mountain. He found himself at the narrow gap between what contemporary climbers know as Eastern Buttress and Scafell Crag. It was here that he began to experience difficulties. He lowered himself down a flight of three granite steps to a narrow ledge. Finding himself unable to continue further down the crag he attempted to retreat the way he had come. To his dismay he found the ledges out of reach and became crag-fast.

Lying on the narrow ledge Coleridge describes entering into a “prophetic trance” (possibly induced by a gram of laudanum) during which he became emboldened by the “powers of Reason and Will”. It was then that he noticed a narrow gap in the rock below him, through which with some difficulty, he was able to pass and thus avoid injury. This gap is known to climbers and hikers alike as “fat man’s agony” and confirms the identity of Coleridge’s descent as Broad Stand.

Inspired by Coleridge’s heroic if slightly foolish adventure, I determined to experience for myself the perils of Broad Stand. Considering discretion to be the better part of valour, and not wishing to become a statistic on the Wasdale MRT website, I decided to employ some professional assistance in the form of a qualified mountain guide.

My rendezvous with Matt le Voi was at the Lake Head National Trust car park early on one of those bright, otherworldly Indian Summer mornings that somehow materialise out of the North Atlantic, surprising the human inhabitants of Cumbria as much as the flora and fauna. Along the well-worn path beside Lingmell Gill, Matt and I strode under the September sun, turning now and again to see how it sparkled off the shimmering length of Wastwater, filling the view behind us as we climbed.

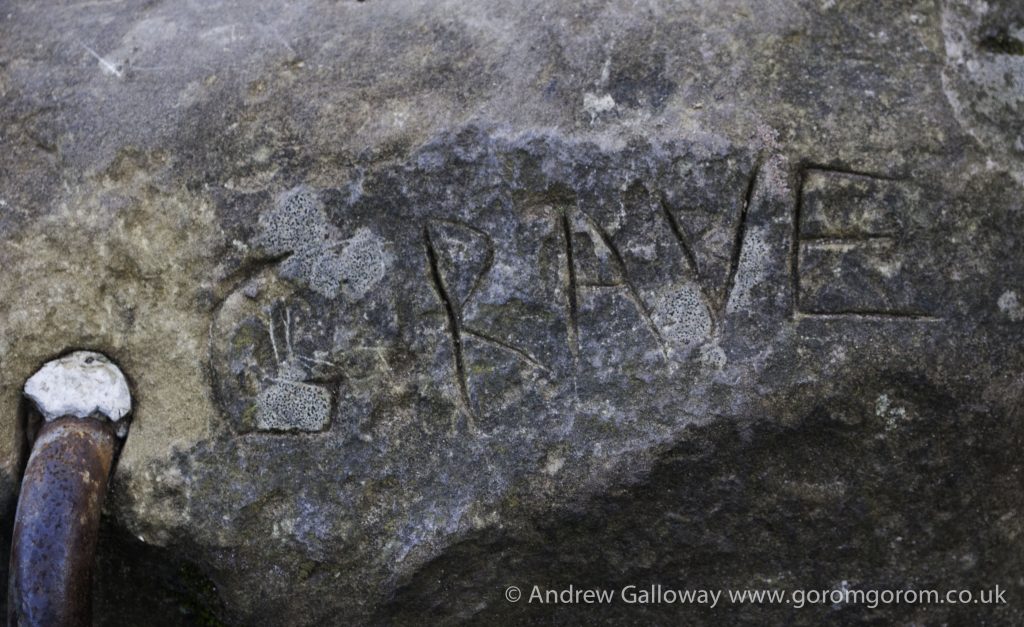

At the approach of Mickledore, Matt suggested we climb the steep scree at the foot of Southern Buttress. Here, carved into the fine-grained andesite of the crag, one can discern the shape of a cross beside which are carved four sets of initials and a date, 21 September 1903. The cross marks the location where four young pioneers of climbing fell to their deaths from the lofty precipice of Scafell Pinnacle above. The names of the four young men killed that day are R W Broadrick, H L Jupp, S Ridsdale and A E W Garrett, all members of the Climbers’ Club, which had been newly founded is 1898. They had been attempting to repeat the ascent of Scafell Pinnacle, which had been first made by Welsh rock pioneer, Owen Glynne Jones some years earlier.

As the late summer sun crept behind the mountain above us, I felt a chill come upon me, the hairs on the back of my neck standing to attention. Here in the highest ‘Corrie’ in England, bounded on three sides by immense towers of rock, stories of tragedy and death gather like the hooded crows that sweep down from the rocky heights.

Just before the outbreak of the First World War, Siegfried Herford, a mathematics graduate of Manchester University, ably assisted by George Sanson, a zoology graduate from University College London, made the first ascent of Central Buttress on Scafell Crag. The crux of the climb was a flake crack, which Herford was able to surmount by standing on the shoulders of Sansom, acceptable practice in those days, precariously held in place by a rope threaded around a chockstone near to the top of the flake.

Siegfried Herford was killed by a rifle grenade in France on the 28 January 1916. Stories of sightings of Herford’s ghost, lingering around the base of Central Buttress, began to circulate among the climbing community thereafter. The mountaineer and author Bill Birkett describes how, in the early 1980’s he was descending from Scafell Pike on a bitter, snow shrouded November day, when, approaching the col of Mickledore he noticed walking towards him from out of the swirling mist, the figure of a young man dressed in Khaki drill. Birkett thought nothing of it until he noticed the man was wearing puttees above his boots, a fashion more readily associated with the British Army of the early 20th Century than the 1980’s. Some years later the notorious chockstone that had held Herford and Sansom in place on Central Buttress, became dislodged and fell, killing the climber Iain George Newman.

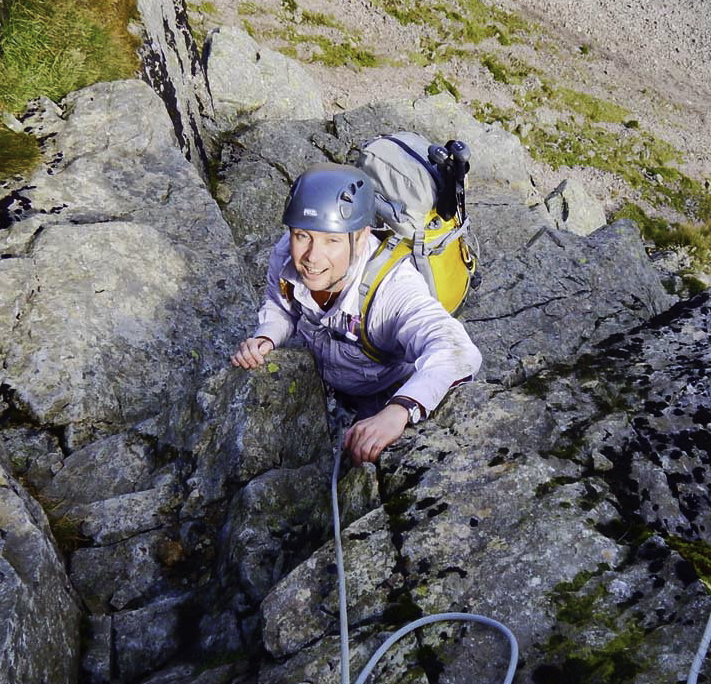

Broad Stand was for once dry. There were no excuses. Aware of the many accidents in this spot we set up a belay from the narrow crack in the seemingly impenetrable defences of Fat Man’s Agony. I watched as Matt disappeared through the narrow gap and found myself alone, the only sounds the clink of karabiners and the down draft of ravens wings. Time ticked away slowly and I began to feel a cramp in my calf, shifting my weight from one leg to the other whilst still maintaining the belay position against the cold grey rock, my knuckles whitening around the umbilical chord of rope threaded through the crevice in the rock. It was a good ten minutes more before I heard Matt’s voice calling down from somewhere above me, informing me that he was safe and I could begin to climb.

Being of slight stature, I was able to squeeze through the vice like fissure in the wall without too much hindrance. I popped out onto the first rock step where with ease I was able to follow the line of Matt’s rope to the left via a series of outward sloping ledges onto the second rock step. Here, my heart surged into my mouth and sweat began to collect on the nape of my neck. With Broad Stand you see, the structure is all wrong – or right – depending on your viewpoint. What first appears to be a series of relatively benign rock steps leading to higher, more manageable ground, takes on an altogether more alarming prospect because of the angle of fracture of the rock, dipping at about thirty degrees to the South. This means that the whole structure leans outwards towards the precipice of the Eastern Buttress, making Broad Stand a bit like the House of Fun at an amusement park, but without the laughs.

It was going to be a leap of faith. I shouted for tight rope and pushed out with all my strength, grappling for the finger hold and finding it securely. “Get a grip!” shouted Matt, and I hauled myself up onto the next ledge, eventually finding my feet on the coarse forgiving granite. I crouched there for some time, regaining my composure and allowing the tide of adrenaline now coursing through my circulatory system to subside, looking down into the heart-stopping drop below.

At the summit of Symonds Knott, lazing under a resplendent blue sky, Matt and I ate a celebratory lunch of cheese sandwiches and chocolate washed down with instant coffee before walking to the cairn marking the summit of Scafell. Turning to the West the early afternoon sun shimmered on the surface of Wastwater as we descended the long, grassy slope of Green How, arriving triumphantly at the National Trust car park, where I thanked Matt for his assistance and waved him goodbye.

Having time to spare I wandered around the head of the lake to Overbeck Bridge where a small shingle beach extended a little way into the lake. There being no one around I slipped out of my walking clothes and into the cold, heart-stopping waters, seeing beneath me the rounded cobbles give way to the bottomless blue of England’s deepest lake. I floated on my back for some time, soaking my heat-sore feet in the mountain clear drink. My gaze scanned the rugged skyline to the East, finding the rocky cleft between the peaks where, not three hours ago, Matt and I had climbed on the very rocks that once had detained Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and recalled the words he had written to his friend Tom Wedgewood.

“I do not think it possible, that any bodily pains could eat out the love and joy, that is so substantially part of me, towards hills, and rocks, and steep waters! And I have had some trial.”

A version of this article first appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of The Great Outdoors Magazine.