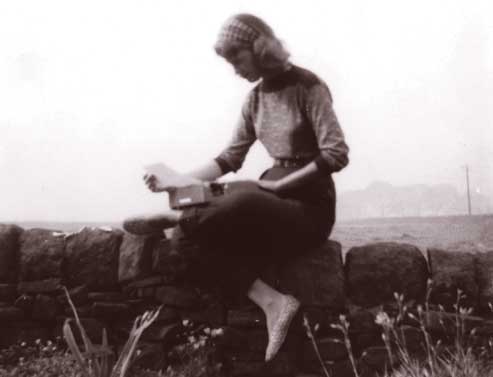

Following the death of Charlotte Brontë in 1855 and the subsequent biography written by Elizabeth Gaskell, published in 1857, there was a surge in popularity of Charlotte and Emily’s novels[i]. As a consequence, a morbid curiosity grew up around the lives of the tragic sisters and the pilgrimage to the parsonage at Haworth, and to Top Withens in particular, became a common undertaking for the literary enthusiast and the down right nosey. The pilgrims came from everywhere: Scotland, Ireland, England, Wales, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, America, all wanting to touch the landscape the Brontës had created. One young American woman came with her new husband and his uncle, Walt, eager in her enthusiasm for romanticism to see the place where Heathcliff and Cathy had roamed the moors. Her transatlantic, almost manic, energy embraced everything with a child-like enthusiasm, as her journal showed. “central tragic figure – Uncle W. – drama of Cathy & Heathcliffe – close.” She made lists of words, Brontë words, stolen from the Parsonage: “luminous – bluish – watercolor – blue book, leather – sofa – Emily died – 19thDec 1848” – in the margin of her notebook she drew a simple sketch of the sofa on which Emily spent her final hours. Uncle Walt showed them the way from Stanbury to Top Withens, where she made a pen & ink drawing of the dilapidated farmhouse, capturing the asperous simplicity of the place, the isolation, the sadness, and the ever-dutiful sycamore trees standing close by. She posed in the branches of one of the trees for a photograph, young, beautiful, vivaciously intelligent, full of life. [ii]

“There are two ways to the stone house, both tiresome. One, the public route from the town along green pastureland over stone stiles to the voluble white cataract that drops its long rag of water over rocks warped round.”

“The other – across the slow heave, hill on hill from any other direction across bog down to the middle of the world, green-slimed, boots squelchy – brown peat – earth untouched except by grouse foot – bluewhite spines of gorse, the burnt-sugar bracken – all eternity, wilderness, loneliness – peat colored water – the house – small, lasting – pebbles on roof, name scrawls on rock – inhospitable two trees on the lee side of the hill where the long winds come, piece the light in a stillness. The furious ghosts nowhere but in the heads of the visitors & the yellow-eyed shag sheep. House of love lasts as long as love in human mind – blue-spidling gorse.”[iii]

Sylvia Path and Ted Hughes met at a party held at the Women’s Union, Falcon Yard, Cambridge to celebrate the publication of a new literary magazine, the St Botolph’s Review, partly edited by Hughes himself. Plath had earlier bought a copy from Bert Wyatt-Brown and had memorised some of Hughes’ poems so as to recite them to him and to impress[iv]. The effect on Ted Hughes was conclusive and their tempestuous relations began, as it was to continue.

“And I was stamping and he was stamping on the floor, and then he kissed me bang smash on the mouth and ripped my hair band off, my lovely red hairband scarf which had weathered the sun and much love, and whose like I shall never again find, and my favourite silver earrings: hah, I shall keep, he barked. And when he kissed my neck I bit him long and hard on the cheek, and when we came out of the room, blood was running down his face.”[v]

Plath and Hughes were married in haste, with a special dispensation from the Archbishop of Canterbury (a waiver of any waiting period or of required residential status) at St. George the Martyr, Bloomsbury on 16t June 1956 – Bloomsday – which was not a coincidence. Finding themselves penniless after the wedding, they move in with Ted’s parents at the family home in Heptonstall, Yorkshire and Sylvia was eager to take this opportunity to explore the wild, barren country of Hughes’ home.

Their visits to Top Withens clearly left a deep impression on both Hughes and Plath, for its image, and the image of the Yorkshire Moors are recurrent themes in their poetry. In her poem, ‘Wuthering Heights’written some years after their stay in Yorkshire, when the pair had moved to Devon, Plath recalls the isolation of the stone house.

“There is no life higher than the grasstops

Or the hearts of the sheep, and the wind

Pours by like destiny, bending

Everything in one direction.

I can feel it trying

To funnel my heat away.

If I pay the roots of the heather

Too close attention, they will invite me

To whiten my bones among them.”[vi]

Sylvia Path died from carbon monoxide poisoning on 11 February 1963, aged thirty; a successful poet with a single novel to her name, ‘The Bell Jar’, published just a month before her death. Her asphyxiation was self-inflicted. Returning to Top Withens years after his wife’s death Ted Hughes recalled their earlier visits, how the small property then still bore the resemblance of a house, how she had excitedly suggested they buy the place and renovate it, how she had sketched, wrote, been wonderful. But twenty years had passed and Top Withens had become an empty shell, devoid of life and character.

We had all the time in the world.

Walt would live as long as you had lived.

Then the timeless eye blinked.

And weatherproofed,Squared with Water Authority concrete, a roofless

Pissoir for sheep and tourists marks the site

Of my Uncles disgust.

But the tree –That’s still there, unchanged beside its partner

Where my camera held (for that moment) a ghost.”[vii]

“It’s twenty years, I’ve been a waif for twenty years! Let me in – let me in!”

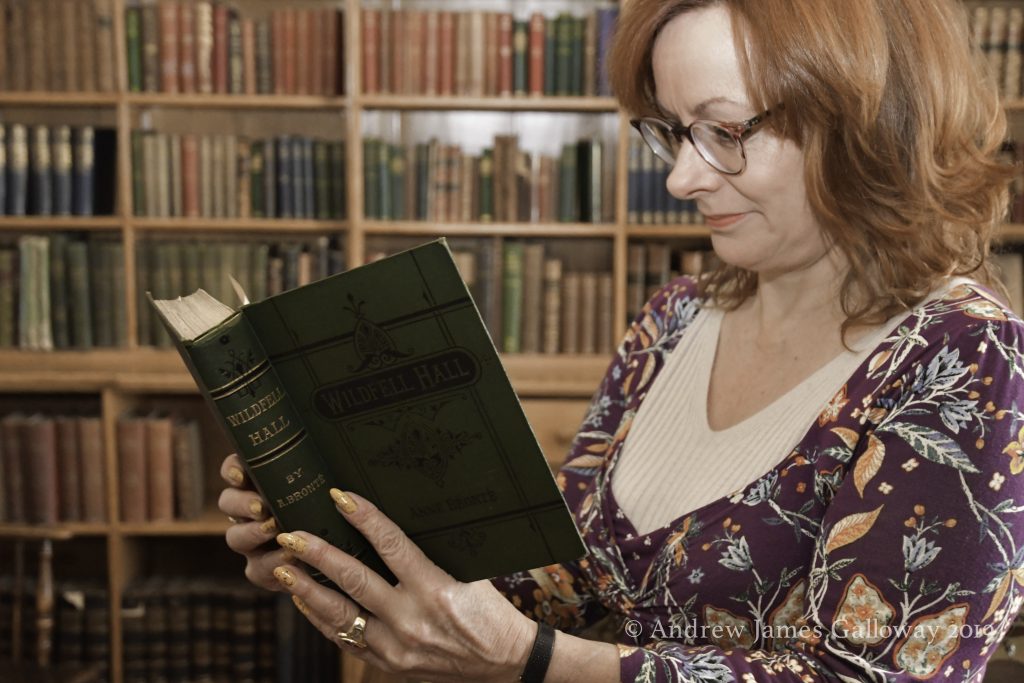

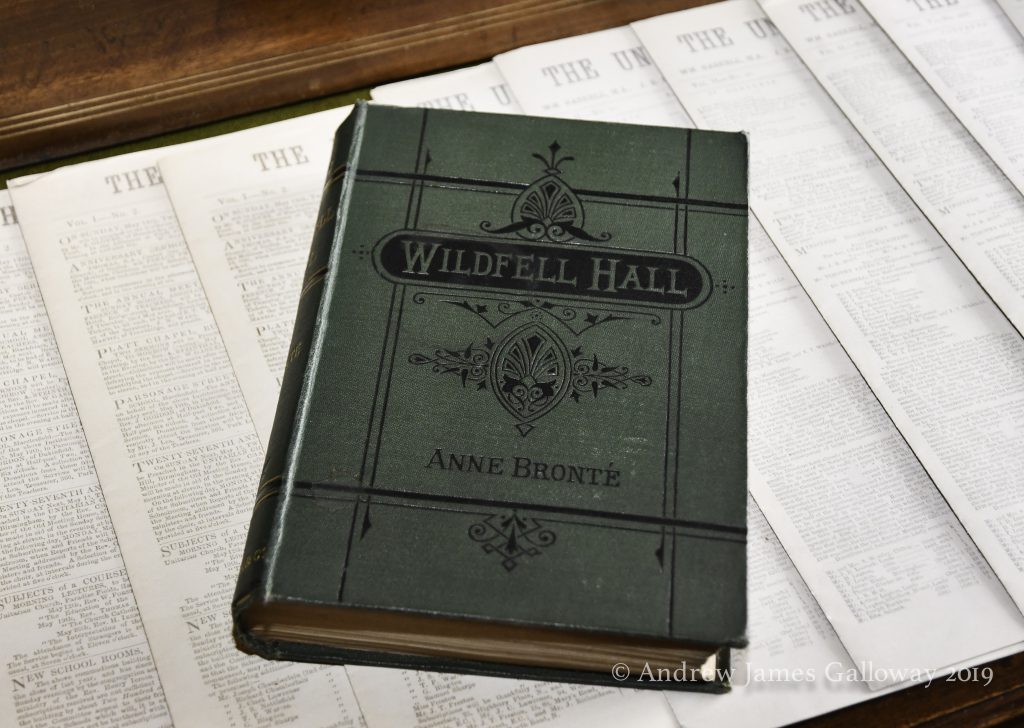

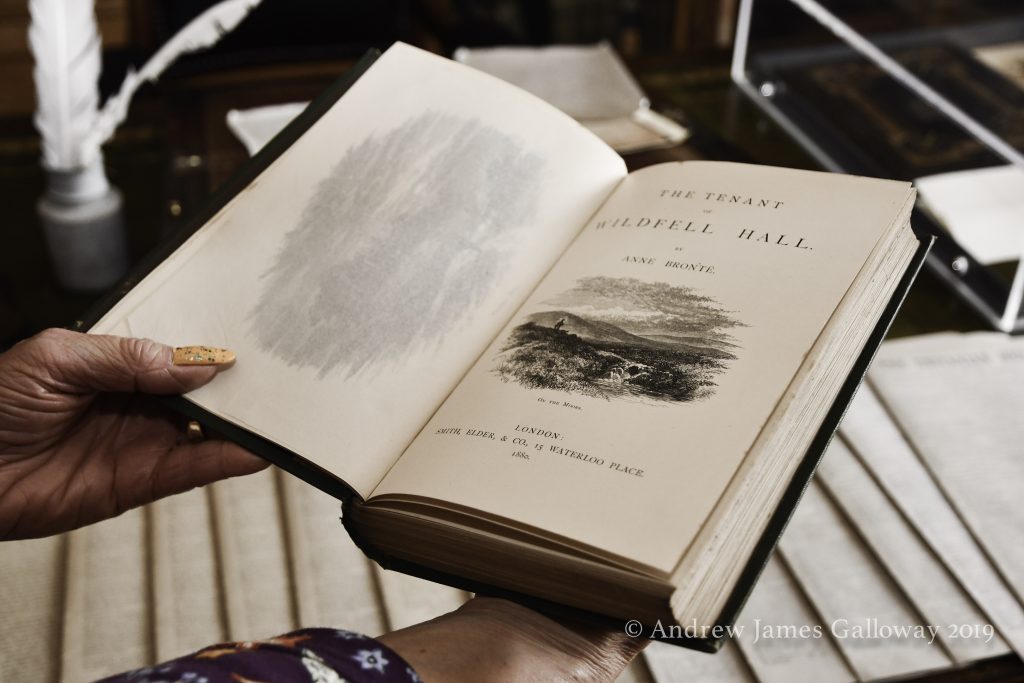

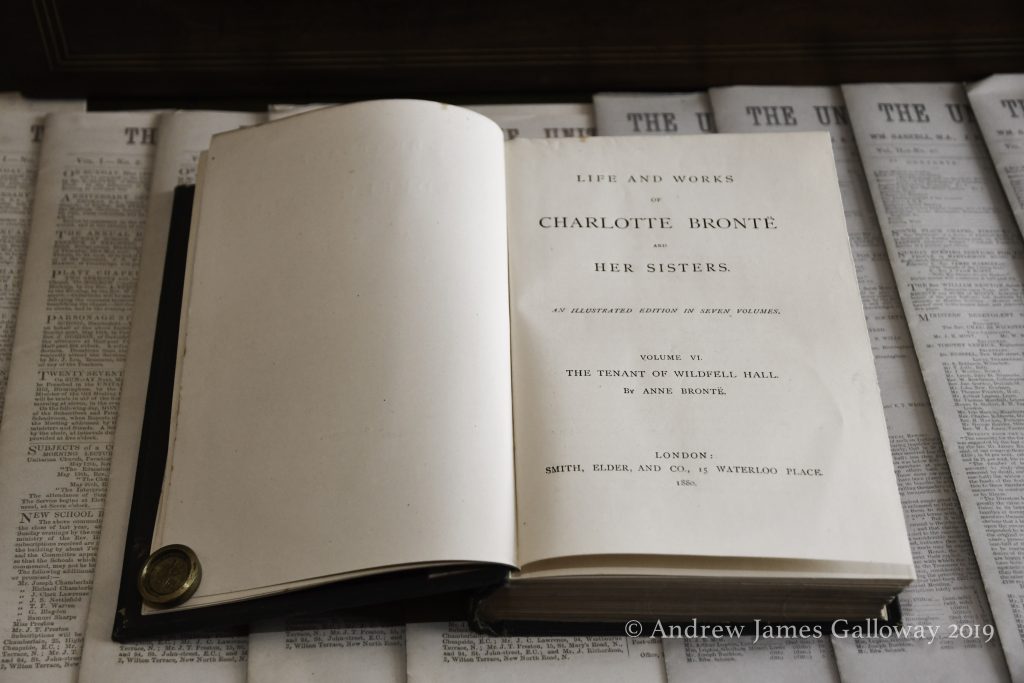

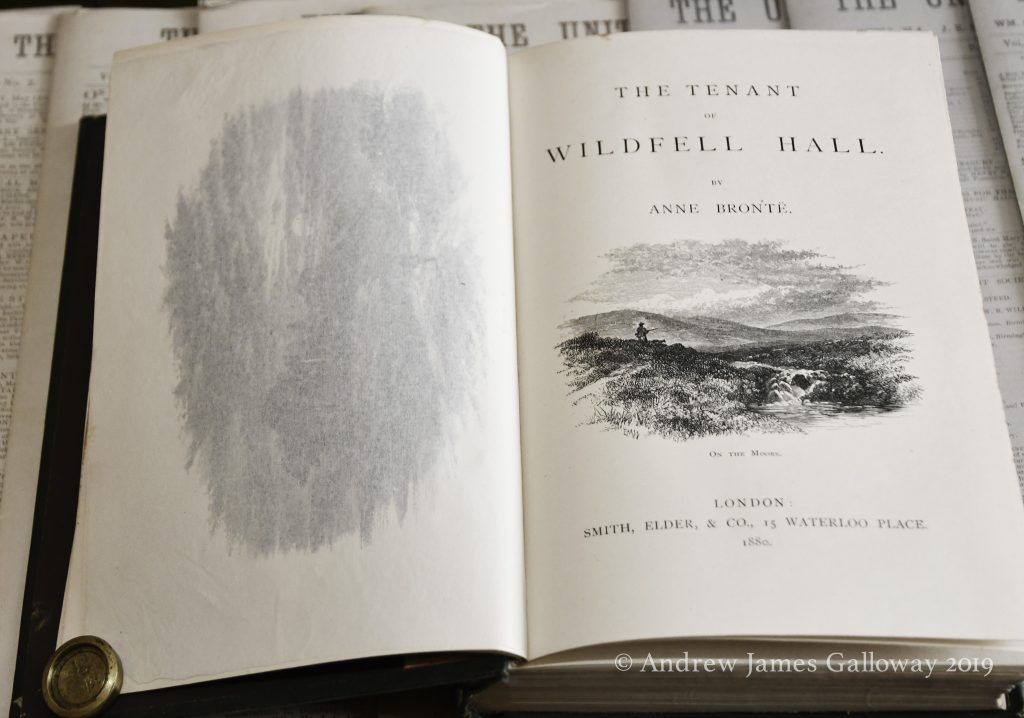

[i]Sadly, Anne’s novels appear to have been mostly forgotten until much later in the 20th Century.

[ii]Stevenson, Anne 1989 ‘Bitter Fame: a life of Sylvia Plath’ Viking Penguin Inc

[iii]Kukil, Karen, V. (ed. 2000) ‘The Journals of Sylvia Path 1950-1962’ Faber & Faber Ltd, pp589

[iv]ibid, pp210

[v]ibid, pp212

[vi]‘Wuthering Heights’, ‘Sylvia Plath, Collected Poems’, Hughes, Ted (ed. 1981) Faber & Faber Ltd

[vii]‘Two Photographs of Top Withens’, ‘Ted Hughes, Collected Poems’, Keegan, Paul (ed. 2003) Faber & Faber Ltd, pp840