The first time I came to Nant Gwrtheyrn I came at night like a broken king. It was late October. I had been walking in Cwm Croesor to the east of Aberglaslyn, exploring the abandoned quarries of Rhosydd and, being underground, had lost track of time. By the time I reached Croesor the light was quickly receding. I recovered my car and drove westwards as the evening spread it raven wings over the sky.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing and with my car poised above the steep, switchback, single-track road that descended into the dark heart of Nant Gwrtheyrn, the thermometer on my dashboard threatening to dip below zero, I cursed my tardiness, wishing for just a few moments of the incandescence that not an hour ago had graced the heavens. Gingerly I threaded the car down the steep track, winding through the dense evergreens until the outline of the quarrymen’s cottages appeared in the glare of my headlights. I killed the engine and was immediately plunged into darkness. I fumbled around in my rucksack for my head torch.

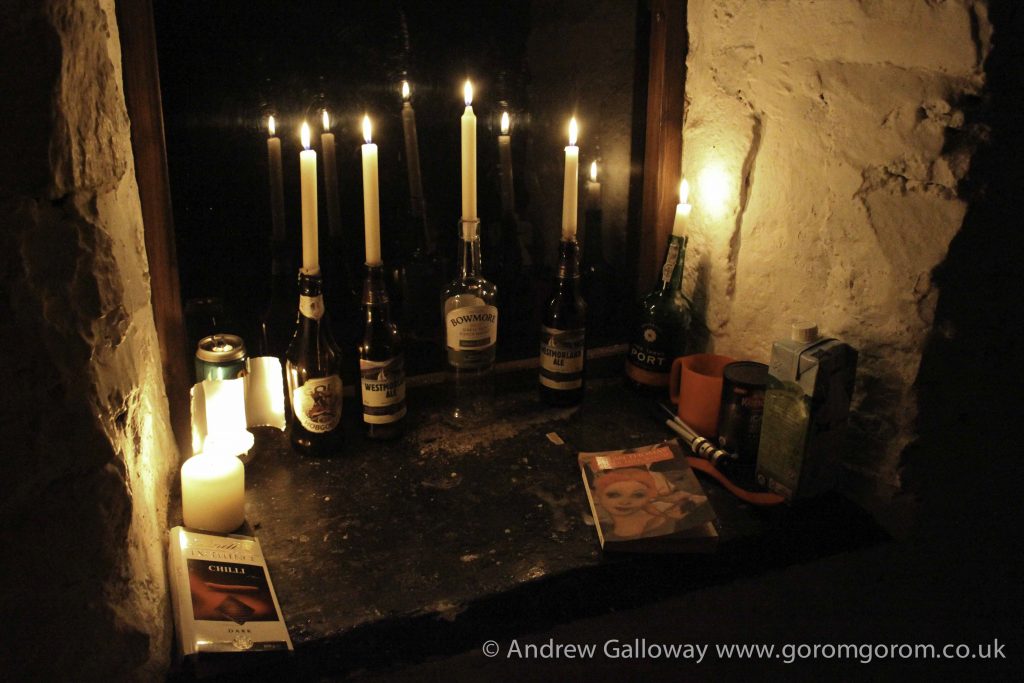

Upon trying the door of the language centre office I found it to be locked, as was the café, the chapel and the bookshop. At just after five thirty on a Thursday evening in late October the ‘ghost’ village of Porth-y-Nant was, not for the first time in its history, utterly deserted. Again I cursed my poor timekeeping. I had told the office staff that I would arrive by four o’clock. I now had the prospect of nowhere to sleep that night. As I considered a drive back to the Victoria Dock in Caernarfon, I noticed, from the corner of my eye, a single light in the window of one of the cottages at the far end of the terrace. I tried the door of the tiny cottage named Arfon and found it unlocked. Inside, on a table by the window, beneath the bedside reading light, a small handwritten note proclaimed “Hello Mr Galloway, Croeso i Nant.” I was touched by the thoughtfulness. The door key had been left on the table beside the note. For one cold dark autumn night too close to Hallowe’en for comfort, I was alone in possibly the most isolated village in Britain.

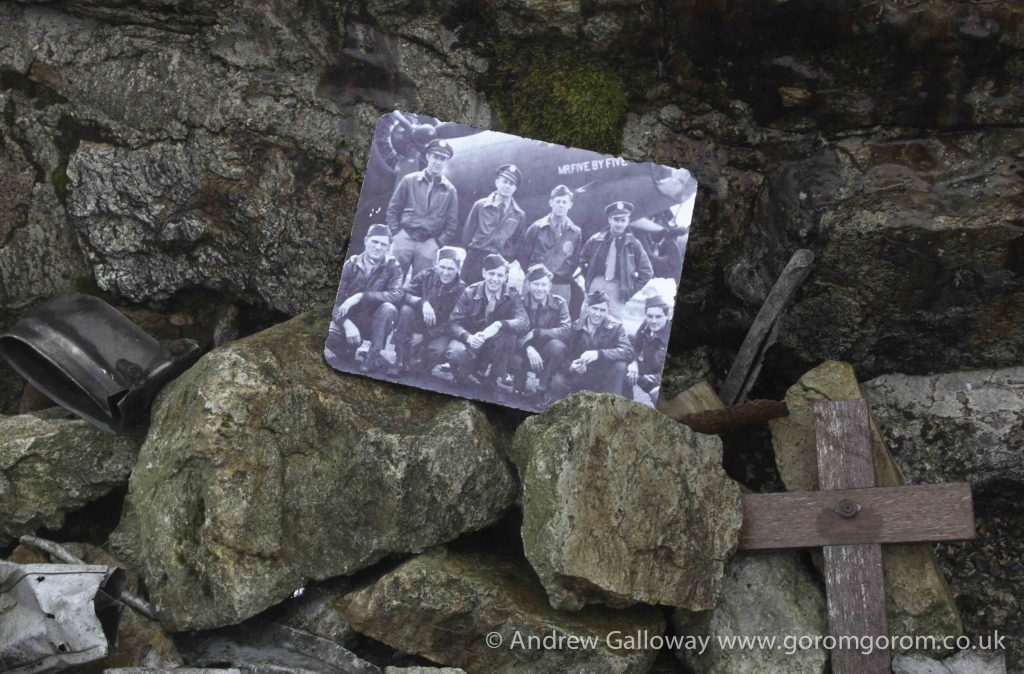

On my most recent visit to Nant Gwrtheyrn I came at midsummer, arriving before four o’clock in the afternoon, the brilliant sun still high in the sky above a silver Caernarfon Bay as I took Bara Brith and Earl Grey at Caffi Meinir. Now better know as a dramatic location for weddings, the original vision behind the restoration of Nant Gwrtheyrn, as imagined by Dr Carl Clowes in 1978, was to create a centre to promote the heritage and learning of the Welsh Language. With the assistance of the local authority of Cyngor Dwyfor, the charitable trust Ymddiriedolaeth Nant Gwrtheyrn was able to purchase the village from ARC Aggregates and basic restoration under the management of the Manpower Services Commission began. The first Welsh course was held ‘yn y Nant’ at Easter 1982, albeit with very limited resources, the village as then not being connected to the mains electricity grid. Restoration work continued and by 1990 all of the original quarrymen’s cottages had been restored to provide comfortable accommodation for guests. The former quarry manager’s house, known as Y Plas, became the focal point for learning. By 2008 over twenty-five thousand people from twenty-seven different countries had visited ‘y Nant’ specifically to learn Welsh.

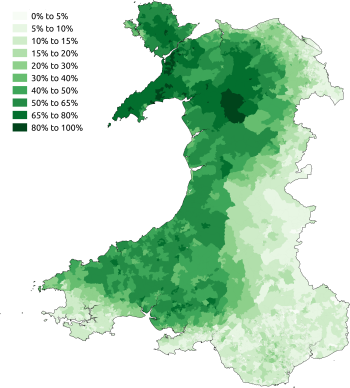

However, despite the success of Ymddiriedolaeth Nant Gwrtheyrn in achieving its core objectives of promoting the Welsh language and creating employment for the local area, the future of the Welsh language is still far from secure. Census figures indicate that although there has in the past thirty years been a small increase in the number of people identifying Welsh as their first language, as a percentage of the total population of the country the figure has marginally fallen, mainly as a function of migration into Wales from England and from the wider European community. Figures from 2011 show that of a population of just over three million people approximately five hundred and sixty-thousand speak Welsh on a regular basis, approximately 20% of the total population. The age group with the highest density of fluent Welsh speakers is the over 65’s.

For many the promotion of the Welsh language is seen as a matter of survival. However, to the vast majority of people living to the east of Offa’s Dyke, the matter is not one of urgency. We live in an age of saturation media where the dominant language is English and, let’s face it, the dominance of the English speaking North American market is only likely to consolidate the worldwide dominance of this language globally. By comparison, the survival of the Welsh language is, as it always has been, very much an up hill struggle. As a former girlfriend, a language graduate from Oxford, used to tell me, the difference between a language and a dialect is that a language has an army and a navy. Perhaps today that army and navy has been superseded by corporate dominance of the Internet.

And what of it? What would we lose if Welsh were to decline into oblivion, as have many other minority European languages? In order to answer that question we need to understand something of the origin of Welsh. Welsh evolved some time in the early sixth century AD from Common Brittonic, the Celtic language spoken by the ancient Celtic Britons. The Brittonic language probably arrived in Britain during the Bronze Age and was most likely spoken throughout the islands south of the Firth of Forth, to the north of which Pictish remained the dominant tongue. English on the other hand is a Germanic language closely related to Frisian, which was most likely brought to the British Isles by one of the Germanic tribes that migrated to Britain during the sixth century AD and ultimately derives its name from the Anglia (Angeln) peninsula in the Baltic Sea. Welsh then has the greater claim to be in direct lineage to what might be described as an indigenous language of the British Isles, although in reality the precursors of what we know today as modern Welsh and English were both brought to the archipelago by immigrants. So much for the pompous bigotry of certain nationalistic political organisations currently extant in British culture. An adequate public education system would do much to banish their xenophobic nonsense forever but such educational investment is unlikely to be forthcoming from establishment ideologies that favour private education and place restrictions upon state education funding and who themselves obtain political benefit from social division and a mind-set of blind nationalism within the population.

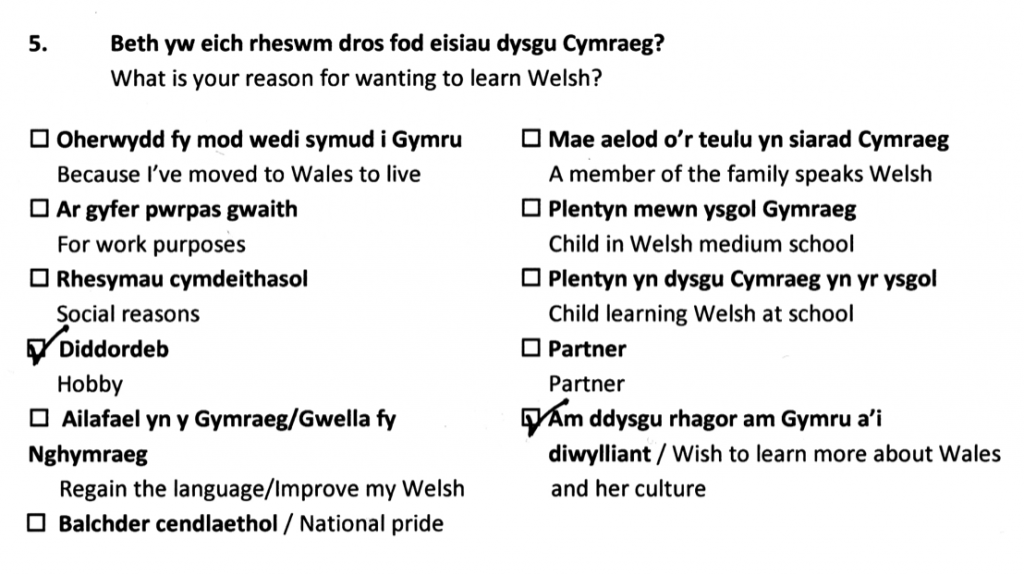

Laying the politics of language aside, the question I am most often asked when I inform people that I am learning to speak Welsh is ‘Why are you learning to speak Welsh?’ Although I often feel aggrieved that I might not be asked a similar question were I to inform said people that I was learning to speak French, Spanish or Mandarin, although given the traditional aversion amongst the English to learning any foreign language there is a fair chance that I would, it is in fact an appropriate question to ask. Appropriate enough for it to be included on the course registration form for prospective students at Nant Gwrtheyrn. However, as a visiting ‘Saes’, of the available options on the form I had to look pretty far down the list to find an appropriate choice. The available options included:

- Because I moved to Wales

- For work purposes

- Regain the language

- National pride

- Child in Welsh medium school

- Partner

- Wish to learn more about Wales and her culture

This left me feeling like a bit of an oddball: a Welsh learner who is not Welsh, who does not live in Wales, who is not in a relationship with a Welsh person, who does not have children attending a Welsh medium school, and does not require Welsh for work. Let me tell you though, I am not on my own. Attending the same course were two ladies from the United States, both as it happens coming from New Mexico although ironically never having met before their trip to Wales. I identified greatly with their desire to learn more about their Celtic heritage and to find something of interest counter to the stream of banal mainstream consumerist culture to which we are subjected daily.

For me however, there are other reasons not provided on the administrator’s list, which during my most recent stay at Nant Gwrtheyrn I pondered for some time. What exactly is it that I am searching for in this strange, alluring, beautiful if sometimes hostile – both in climate and culture – country located less than forty miles to the west of the place where I was born?

In his book History on our Side, a memoir of the 1984-1985 miner’s strike in Wales, Hywel Francis speaks of a collectivism and sense of community throughout the South Wales Valleys, the spirit of which saw those communities through months of what could only be described as state persecution. It was of course this collectivism and sense of community that Thatcher set out to crush in the 1980’s. The miners’ strike had little if anything to do with uneconomic pits.

Set against the harsh reality of post-Imperialist, post-Thatcherite, post-Brexit Britain it is perhaps easy for me to view Wales through rose tinted glasses, to make of it a type of Shangri-la for a dispossessed idealist. None-the-less I still see something of that sense of collectivism and community in parts of Wales, the enterprising ventures of Carl Clowes at Nant Gwrtheyrn being a case in point. It is a culture that for me stands out against the vacuity of the post-imperialist individualism propagated by corporate Britain and its establishment benefactors. In truth this individualism is nothing more than the denigration of individuals into units of consumption, who more often than not render themselves addled by cheap alcohol and bloated by junk food. I see that we have now reached a point where neo-capitalist ideology, neo-liberalism, Thatcherism, call it what you will, is so engrained in the consciousness of the British people that nothing is seen to have value unless it creates wealth. In this respect learning Welsh will always be seen as a fancy, an addition to a wish list subject to available funds (always, of course, in limited supply).

It would be easy for me to wax lyrical about my relationship with this curious nation, especially as I have for much of my life chosen to remain in England to take advantage of the economic security of life there. None-the-less, the history, culture, people, places and yes, the language of Wales have figured large in my past, continue to do so in my present, and, God willing, will do so for many years to come.