Paradise on the Pike by Sarah Angleton

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

The early twentieth century was a critical time for the USA. The transition from a “developing” nation to a global super power was exemplified by the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, or the St Louis Worlds Fair as it was informally know, held in 1904, ostensibly in commemoration of the acquisition of 800,000 square miles of land from the French Republic a hundred years earlier.

The narrative of Paradise on the Pike draws on two themes associated with the exposition, race and imperialism. The protagonist, Max, is an recent immigrant to the USA from rural Prussia. He and his mother have fled unfortunate circumstances in their homeland to settle among relatives in St Louis. At first Max is like a fish out of water, but he soon acquires a basic grasp of English and is hired as a construction worker at the site of the World’s Fair to be held in St Louis later that year.

Through a chance meeting Max is offered work at Hagenbeck’s Animal Paradise, one of the exhibits at the fair. He is put to work tending to the various exotic animals on display, and through the course of his duties meets and falls in love with Shehani, a beautiful young dancer from Ceylon.

All is going well for Max but for a thorn in his side in the shape of the dastardly Pete Williamson, the American business partner of the Hagenbecks, an ego-centric chauvinist who likes to boss Max, and just about everyone else at the exhibit, around.

When the partial remains of Williamson are discovered in the Alligator pool and suspicion is directed at the Ceylonese dancer, Max turns private detective in an attempt to prove Shehani’s innocence.

Weaving together historic fact and page-turning fiction, Paradise on the Pike is a must read for anyone with an interest in the history and politics of the United States.

View all my reviews

Jesus & Justice: Stories of radical Christian living by Red Letter Christians UK

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Jesus & Justice is a collection of essays written by British Christians from a variety of denominations and traditions, all of whom have all been inspired by their faith to engage in projects of social justice.

The essays are nominally collated around themes found in the book of Isaiah, Chapter 65, verses 17 to 25, which begins as follows:

The Glorious New Creation

For I am about to create new heavens and a new earth;

the former things shall not be remembered or come to mind.

Many of the essayists express how at certain times in their ministry they have felt pressure to measure their discipleship on the basis of success, often in outcomes of numerical attainment: how many people attended, how many “saved,” how many groups or programmes launched. In most cases the concluding ethos is that discipleship is more about making a genuine, grass-roots connection with people in the places in which they live and work, rather than any aggregation of numbers.

Stand out contributors were Mandy Bayton, writing about her experience of running a shelter for the homeless, and Steve Chalke writing about secure schools as spaces for transformation, the verity of their witness leaving me at times verklempt.

I particularly enjoyed the scripted discussions at the end of each section and the reflective questions. These provided a welcome hiatus in what otherwise might have been a rather daunting collection of essays.

Critically, I would have appreciated a wider theological perspective on the nature of injustice and its seemingly ubiquitous prevalence in human social structures. Perhaps for another volume at another time? A minor point, but section headings on the contents page would be helpful, perhaps taken from the verses from Isaiah that precede each section.

Overall, this is an engaging volume offering testimony of some inspirational lived experience of Christian discipleship. It certianly makes a change from another book on dry theology.

View all my reviews

Off-Beat Spark by David Hardy

Off-Beat Spark is the first volume of poetry by Marple based poet David Hardy. A relative newcomer to the Greater Manchester poetry scene, David takes us with him on a magical mystery tour through his own off-beat perspective on the human condition, artfully shifting between keenly observed slice-of-life encounters, humorous anecdotes, moments of pathos, literary & musical reflections; a veritable smorgasbord of contemporary suburban life.

David’s most obvious talent is with rhyme. Without recourse to rhyming dictionary, or so I’m told, he uses rhyme to draw the reader into the poem, deftly avoiding extremes of cliche and ostentation. This example is from Black, Red, Green, Blue:

“The infinite universe above

With stars you can almost feel

The attire at a funeral procession

Or a Henry Ford automobile

Tarmac smouldering on the highway

Rhymes with Jack Kerouac

He’s on the road again

And never will come back.”

As felicitous as it no doubt is to performance poetry, David’s allegiance to the traditional ballad form of quatrain iambic tetrameter can, for the reader, induce a little fatigue. For his second volume I would encourage him to broaden his repertoire of poetic form, perhaps treating us to a Sonnet or two, or even a Villanelle.

None-the-less, Off-Beat Spark is an undoubted achievement, a blessing too, gifting us a window into the mind of that most rare of beings, a man in possession of an innate sensitivity to to the world around him and the power of imagination to put that into words. I guess that’s as good a definition of a poet as I’m likely to find anywhere.

The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty by Sebastian Barry

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I certainly enjoy Barry’s use of Irish vernacular in his prose, though as others have mentioned, it can be a little over done at times. I’m not sure I can forgive his the use of “of” in place of the possessive “have” both in his prose and reported speech here, although I see it was very much done deliberately for effect.

As for sentimentality, well yes, the reunification of Eneas and Teasy in “heaven” is a little syrupy, but I’ll forgive him.

Is Barry a Dylan Thomas fan? His vernacular prose seems to me at times to echo the great poet. And speaking of allusions, the entire novel, for me, seems to hinge on the reference to Revelations 20:15, to which he makes reference several times in the narrative and in the final paragraph of the book. I like the idea of Barry’s suggestion that there are no names written in the “book of life” or perhaps all our names, which is the same thing, and that ultimately, the consciousness we possess so briefly is all too soon thrown into the lake of fire, but that the lake of fire into which we are thrown is the burning eternity of the cosmos.

Bravo. I’ll try the Roseanne McNulty tale next.

The Salt Path by Raynor Winn

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I’d seen a lot of hype about this book so my expectations were high. Right away I was disappointed to find it a pretty perfunctory non-fiction memoir rather than a novel. In the first few chapters I was assaulted by erratic prose that lacked fluidity, poor punctuation, poor syntax and an over-use of rhetorical questions. Winn seemed to harbour resentment to any person or institution that did not fit into her radical view of the world. Now don’t get me wrong, I have a sympathy for radicalism myself, but feel in non-fiction prose it is better to present facts and events rather than opinion. It shows naivety in a writer to assume that the reader will share their opinion on a subject.

None-the-less, there are moments of poetic beauty in Winn’s prose. It was the passages where she allowed her awe and wonder at nature to speak through the political rhetoric that kept me reading to the end.

The first eight chapters would have benefited from further editing. I imagine Random House chose not to do this so as to retain more of Winn’s voice, but I feel that too much of her, perhaps understandable, resentment spills out onto the page and so distances the reader from the emotional impact of the book.

View all my reviews

The Manchester Man by Isabella Varley Banks

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Isabella Bank’s Manchester Man is very much a didactic novel of the late nineteenth century. In terms of depth of character, Jabez Clegg is a little too good to be true. As Pope said, ‘to err is human’ but as Banks would have it not to err is Clegg, though she does perhaps make some acknowledgement of his quasi sainthood when the anti-hero of the novel Lawrence Aspinall tells us that ‘Mr Clegg is the white hen that never lays away.’ If Clegg is the saint of the piece then Aspinall is his counterpoint, his nemesis, the classic nineteenth century privileged rouge. He is akin to Anne Brontë’s Arthur Huntingdon, so much so that one wonders if the latter character did not inform the former.

Clegg’s social advancement at the behest of the wealthy Ashton’s sticks in the craw somewhat by modern standards, suggesting as it does that the working class may only advance with the moral approbation of the great and the good, although in Bank’s defence, in the early nineteenth century society probably did function in this manner. Perhaps to some degree it still does.

Augusta Ashton’s swooning over the handsome sociopath Aspinall is unfortunate if not entirely without precedence. She is not the first naive young heroine in English literature to fall for a flashing blade only later to find that blade has cut her to the quick. Catherine Earnshaw and Helen Huntingdon I’m looking at you.

The novel makes much use of Lancashire dialect and colloquialisms, many of which now sadly missing from the modern metropolitan nasal Mancunian drawl. There is also much historical content including a gruesome account of the Peterloo massacre which took place on 16 August 1819 and the sinking of the Emma, a river flat ship resulting in the loss of 47 lives. Jabez Clegg’s forgiveness of Aspinall’s sabre attack on him at Peterloo, an assault which could so easily have resulted in Clegg’s death, seems contrived by modern standards, more so that the drunken state of the assailant should be taken as legitimate mitigation.

Although perhaps overly didactic and formulaic, The Manchester Man has much to offer as a dramatic account of early nineteenth century life in the North of England. Jabez Clegg’s tumultuous ride down the River Irk in his painted cradle is in many ways the creation myth of a city.

View all my reviews

An Instance of the Fingerpost by Iain Pears

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Having the audacity to tell the same story from four perspectives, it is some achievement that Iain Pears keeps the reader guessing until the very final chapters of a novel encompassing no less than seven hundred pages. He has perhaps allowed a little sentimentality to possess his pen in the conclusion to the fate of Sarah Blundy, but then before we are halfway through the last of the accounts, made by the Oxford historian Anthony Wood, we have either suspended all disbelief or have abandoned the book altogether. And whether or not we subscribe to the Montanus Heresy it provides a far more satisfying conclusion than dismemberment. At which point I must quickly turn about for fear of spoilers.

At seven hundred pages this is a long read for a novel and one that at times seems longer due to the unpleasant character of two of the four narrators. Pears makes such extensive use of the unreliable narrator trope that at times he risks losing the empathy of the reader altogether. It is a relief when the narrative baton is passed to Anthony Wood and the so far disconcertingly baffling story is finally given some semblance of humanity and cohesion.

Pears’ evocation of England in the Seventeenth Century is achieved with equal measure of subtlety and brutality leaving the reader at turns heartbroken, revulsed and overjoyed. In short Fingerpost is one of the finest historical novels I have read.

View all my reviews

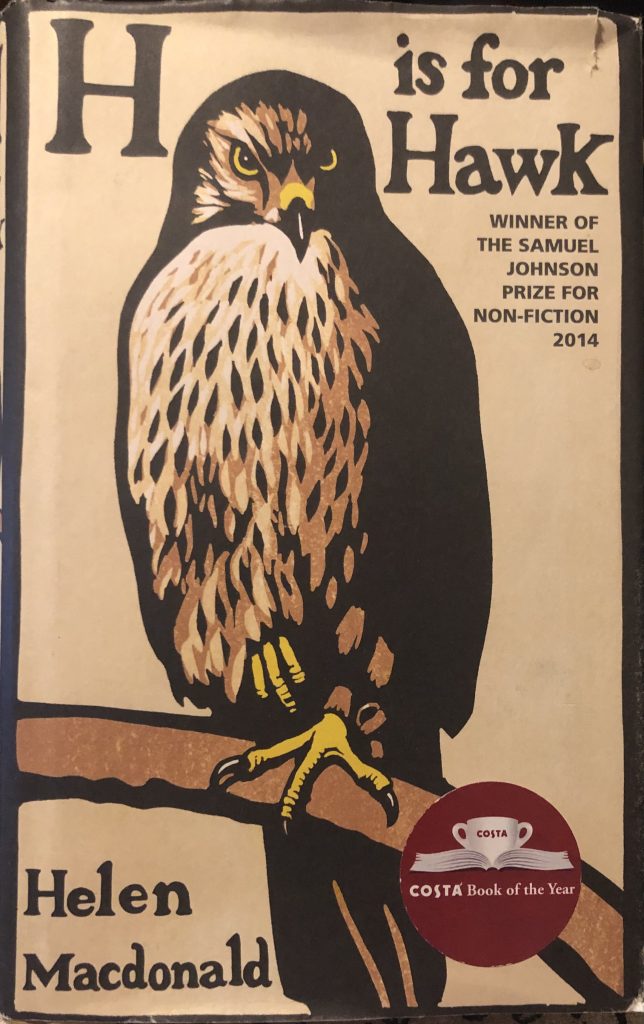

H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

At first I was deeply suspicious of this book. Not least the reek of Cantab privilege, I also felt Helen MacDonald’s fascination with T H White and the pleasure she so obviously derived from the instinctual brutality of the hawk to be disconcerting. Acutely aware of White’s sadism, at times she could barely contain her own.

However, Helen’s at times beautifully crafted prose kept me interested for long enough to see the humanity seeping through her agoraphobic tendencies. I am still not entirely convinced this is true nature writing, despite the ample plaudits from the great and the good littering the dust jacket. It seems to me that Helen spent most of her story trying to prevent Mabel from being truly wild.

View all my reviews