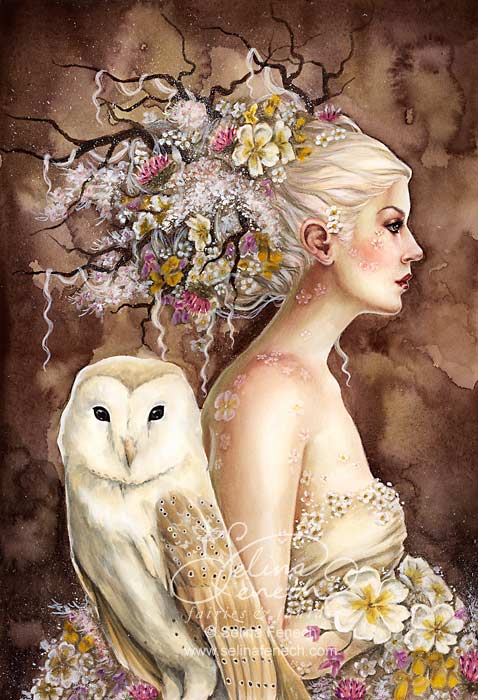

“She wants to be flowers, but you make her owls, and she is for the hunting.”

Alan Garner, The Owl Service

Lleu Llaw Gyffes stood upon the rocky outcrop shot through with obdurate, milk white quartz, high above the cascading waters of Afon Cynfal and raised high above his head his fire-forged spear. With every sinew, every muscle and tendon in his body taught with indignant rage, he aimed his lance at the heart of Gronw Pebyr, lover of his wife, usurper of his crown and author of his downfall.

Such is the culmination of a folk tale that over centuries has woven itself into the consciousness of the Welsh nation and the fabric of a landscape. The evocative story of the love triangle between the heroic but gullible Lleu Llaw Gyffes, the devious Gronw Pebyr and the beautiful flower maiden Blodeuedd, manifested into existence by the magician Math son of Mathonwy, is part of a narrative with origins believed to date back to the post-Roman period of British history but which has become known as the Mabinogion, a collection of medieval folk tales of the Welsh corpus, translated into English and popularised in the early 19th Century by Lady Charlotte Guest. The tale of the entanglement of the three lovers is unique amongst the collection in that many of the geographical locations of the story can be identified in the landscape of Snowdonia and in particular the secluded valley of Cwm Cynfal which lies some miles to the south of Blaenau Ffestiniog, Gwynedd.

At the edge of the forest there were scenes of devastation wrought by the winter storms. Over a dozen large Sitka Spruce lying vanquished across the saturated forest track. With a little persistence I was able to clamber across the fallen timber and make my way over the river by means of a small footbridge. Further along the valley, in the centre of a long narrow farm track, I came upon what at first I thought was a sleeping cat, but which upon closer inspection I found to be a young lamb, cold and curled up upon itself; dead, I assumed, abandoned by its mother. I felt I couldn’t leave it where it was to be squashed by the next Mitsubishi to come blistering down the track, so I resolved to move the cadaver into the thicket and let the carrion crows do the rest. As I touched it, the little thing revived, its eyes thick with mucus, its head lolling like a rudely awoken drunk, reeking of the sour stench of death – if not already off his mortal coil, this little one was not far from it. I checked my map and saw there was a farmhouse not a mile further along the track and so despite the mucus oozing from every orifice and the smell stronger than a hikers sock, I took up the lamb in my arms and set off towards the farm.

Fferm Cwm, 1497 read the sign. A simple but beautiful oak-beamed ‘A-’framed building with a low oak door and an elaborate iron knocker which I raised and let fall loudly. There was no answer. I knocked again, fully expecting a gruff, septuagenarian, hard-minded, Welsh speaking hill farmer with little time for sentimental Englishmen and half-dead lambs, to answer the door. Instead it was opened by a fashionably dress young woman, hair held up with a decorative broad headband, wearing a designer sweater, bright purple leggings and “Ugg” boots. I assumed a holiday let. “Hi”, I said, feeling rather foolish now standing at the door covered in mud and sheep mucus holding a half-dead lamb. I asked if the sheep were her responsibility. She answered in the affirmative, sounding a little vexed, and invited me in.

The lady led me through to a lounge, which took up most of the ground floor of the building. The walls were paneled with wood, bamboo matting covered the stone floor and thick oak beams held aloft the ceiling. But for the large flat-screen television in the corner of the room showing an omnibus of Hollyoaks, I might have walked into a medieval hall. By the fireplace lay another invalid lamb, feeding on freshly cut grass. The lady of the house took my lamb and placed a plastic cover over him and fed a feeding tube into his gullet so as to administer a glucose solution. He was then treated to a gentle warming from a small hairdryer and placed in front of the fire with the other lamb for company and the afore mentioned television for entertainment.

The lady of the house I discovered was Bronwen, whose father had owned the farm for over forty years but who had sadly died some months earlier. He had been a professor of art at Bangor University and Bronwen had grown up at Fferm Cwm but had moved away to Liverpool in later life. Following the death of her father she inherited the farm and the two hundred sheep that came with it. Initial plans to sell the farm were complicated when the two hundred sheep came into lamb during the spring and something had to be done so she and a couple of friends upped sticks from Liverpool and took up residence as temporary shepherds in Cwm Cynfal.

Conscious of my boots dripping mud onto Bronwen’s bamboo matting and happy that my little rescued lamb was in the care of someone who was actually capable of restoring him to life, I made my excuses and carried on my way eastwards to the cascades at the head of the valley.

Gronw Pebyr, Lord of Penllyn was hunting in the forest of Hafod Fawr when late in the evening he came upon Mur Castell, the court of Lleu Llaw Gyffes, who was absent at the time at the court of the magician Math son of Mathonwy, having left his wife Blodeuedd in charge of affairs. Concerned that her husband would be unpleased if hospitality was not offered to the lord, Blodeuedd invited Gronw and his entourage to stay the night at the castle. However, as soon as Gronw entered the castle and his gaze fell upon that of Blodeuedd, were they both filled with the deepest love for each other and sought that very night to consummate that love in each other’s embrace. Rather than take leave from his host the following day, Gronw sought to stay a further night in his lovers arms and together they conspired how they might rid themselves of Lleu Llaw Gyffes.

Some days later Gronw departed and the lord of the house returned. That night Blodeuedd feigned concern for her husband’s life. Lleu replied that she had little to fear for by virtue of his birth, his mother being the sorceress Aranrhod, daughter of Dôn, it was all but impossible to slay him. Blodeuedd pleaded with Lleu to tell her that way in which his death might come about, so as she may always ensure that such circumstances should never occur. Foolishly, Lleu agreed. Firstly, he told her, any spear able to strike the mortal blow would have to be forged only when people were at Mass on the Sabbath and be a year in the making. Further, a bath of stone would need to be made on the riverbank and that with a thatched roof and by bringing a Billy goat along side the stone bath so as Lleu would place one foot on the edge of the bath and one foot on the back of the goat. Only then could the mortal blow be made. Blodeuedd laughed nervously, for she knew such circumstances were never to occur by chance. None-the-less she sent word to Gronw Pebyr who immediately set about making a spear in his forge.

A year later Blodeuedd entreated her husband to again regale the details of how his mortality may come about and to demonstrate the same. In order to please her he agreed and so she prepared a stone bath with a thatched roof on the banks of the river Cynfal and gathered as many Billy goats as she could find in the valley and sent word to Gronw Pebyr to make himself ready under the lee of the hill known as Bryn Cyfergyr which overlooks the river. Then Blodeuedd asked her husband to show her the position in which his mortality may be taken by placing one foot on the edge of the stone bath and one foot on the back of one of the Billy goats, and again, foolishly, to please her, he agreed. No sooner did he do so Gronw Pebyr rose up from behind Bryn Cyfergyr and threw the year-forged spear at Lleu Llaw Gyffes such that it struck him in the side, whereafter Lleu leaped into the air in the form of an eagle issuing an ear piercing scream, flying away into the mountains of Eryri.

Beyond the meadow to the east of Fferm Cwm the ground rises steeply to a spur with a natural viewpoint above and the Afon Cynfal tumbles over a series of cascades culminating in the dramatic Rhaeadr y Cwm with a drop of thirty-seven metres over Ordovician shale and sandstone turbidites. Above the cascades the landscape broadens out into open moorland, much of which is above five hundred metres in height. There is a lot of open space up here on the edge of Yr Migneint, an expanse of blanket bog of over two hundred square kilometres, the most extensive in Wales. Sadly, the remoteness of this landscape has encouraged its exploitation for the management of utilities. A line of electrical grid pylons now transect the forest plantations of Hafod Fawr, strung together like enslaved giants, striding westwards to the controversial (it being located in the national park) and since 1991 decommissioned nuclear power station of Trawsfynydd, the presence of all of which somewhat detracts from the sense of wilderness. As I wandered south from Pont yr Afon Gam towards the forest I was struck, as I often am in such places, by the emptiness of the terrain. As I climbed up onto the undifferentiated summit of Pen y Foel-ddû the sense of isolation just grew and grew.

The Ramblers Association have for some time expressed concerned that since the passing of the CROW Act in 2000 the use of open access land has not been embraced by those who engage in outdoor activities as perhaps was expected. This may be due to several reasons, not limited to a lack of confidence in navigation skills, over-dependence on GPS units, guide books which still slavishly stick to established rights-of-way and perhaps more than any other, the fear of getting lost. In her book “A Field Guide to Getting Lost”, Rebecca Solnit laments the disappearance from our maps and atlases of the term ‘Terra Incognita’. With our reliance on technology, we in the 21st Century often rest under the assumption that no region of the globe, no square kilometre of our planet, remains unknown, for everything is photographed and mapped by satellites, charted and measured by global-positioning systems. Something the tragic disappearance of the Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 must remind us all is that this protective veil of technology is not infallible.

Solnit argues that any map only provides a restricted view of a particular landscape, limited by the information left out: the unmapped and unmappable. We may look at the Ordnance Survey map of the Vale of Ffestiniog, look at the ochre contour coils against the pale yellow patches between reference squares 7138 and 7642 and notice the lack of little black or green dotted lines there, but unless we take our compass in hand and step out into those contours, to all intents and purposes they remain ‘Terra Incognita’, their story forever silent.

Nineteen hundred years ago this moorland may have bore more trees, but perhaps this broad, open landscape and sense of isolation was what drew the Roman Legions to use the area for training camps. Where the Afon Llafar tumbles down from the twin lakes of Llyn Conglog-mawr and Conglog-bach are remains of many Roman practice works. It was common, when moving large numbers of troops across hostile territory, to build fortifications overnight and raw recruits had to be trained how to do this efficiently. Here too, passing Dolbelydr, Sarn Helen, the main Roman artery through occupied Welsh territory, climbs towards the Roman complex at Castell Tomen-y-mur, in its time the most extensive Roman complex in Wales comprising a military tertiata fort of over four acres, a stone built principa, annexe buildings and even a small amphitheatre for troop entertainment. When the Roman legions withdrew from Britain, the territory left behind fell into the hands of tribesmen and warlords. The presence of a Norman motte here indicates that the site was variously occupied until around the early twelfth century and the ruins of a hafod, a small farm dwelling, indicate that the site was occupied for agricultural rather than military purposes well into the nineteenth century. But today the once centre of Roman provincial power, Mur Castell, the court of Lleu Llaw Gyffes, as imagined in the Mabinogion, is occupied only by sheep who ruminate on the abundant thistles.

And so Gronw Pebyr wasted no time. He returned victorious to Mur Castell and with Blodeuedd by his side took possession of the lands of Ardudwy, which once were the province of Lleu Llaw Gyffes. When Gwydion, Lleu’s uncle heard of his fate he was greatly distressed and set off to search for his wounded nephew. Through all the country of Gwynedd and Powys he searched until he came to a valley where he saw a sow feeding on rotting flesh and maggots beneath a great oak tree. When Gwydion looked up into the tree he saw a wounded eagle resting in the upper branches and every time the eagle shook itself, the rotten flesh and maggots would fall from his wound and so the sow ate them. And so by means of singing an enchanted song to the bird, Gwydion was able to entice it down from the tree whereupon he struck it with his magic wand and Lleu Llaw Gyffes was restored to his former shape, yet gravely ill.

After many months recuperation Lleu Llaw Gyffes mustered an army and set out to Ardudwy determined to reclaim his lands. Upon hearing of his coming Gronw Pebyr and Blodeuedd fled, Gronw to Penllyn and Blodeuedd into the mountains with her maidens, who, being so filled with fear would only walk backwards and so fell into a deep pool and were drowned, that lake now bearing the name Llyn Morwynion, the lake of the maidens. As for Blodeuedd, when Lleu finally caught up with here he intended to kill her for her betrayal, but was none-the-less filled with love for her and instead transformed her into the shape of an owl, a bird so cursed that she may only hunt at night and towards which all the other birds were filled with enmity. And her name was henceforth known as Blodeuwedd, Flower-face.

Gronw Pebyr appealed to Lleu Llaw Gyffes for clemency in exchange for silver and gold, but Lleu would have none of it and instead requested that Gronw meet him by the cascades upon the river Cynfal and receive from him the same blow that Gronw had unleashed upon Lleu. Gronw reluctantly agreed, and so they both came to the banks of the river and Gronw stood by the stone bath on the banks and Lleu Llaw Gyffes took up position under Bryn Cyfergyr and aimed his spear at the heart of Gronw Pebyr. Wait! shouted Gronw, pleading with Lleu for clemency, that as he had not acted alone in his deceit he be allowed to place a stone, which he saw by the river bank, between himself and the spear. Lleu Llaw Gyffes agreed and so Gronw Pebyr held the stone before his chest and Lleu Llaw Gyffes threw his spear with all of his strength and the spear pierced the stone and Gronw’s chest and broke his back and he fell to the ground dead.

And should you care to, you may wish to visit, on an overcast, rainy afternoon, an innocuous, rather muddy field, populated by indifferent sheep, above a farm known as Bryn-saeth, the hill of the arrows, and find under the dripping hawthorn Llech Gronw, the stone of Gronw Pebyr, with a hole right through the middle of it made by the spear of Lleu Llaw Gyffes. And as you walk from the stone, as the light beings to fade and the gloaming gathers amid the oak trees of Cwm Cynfal, you may hear the cry of an owl as she mounts her nightly hunt.

An abridged version of this article appeared in The Great Outdoors Magazine