“Great novels offer us not only a series of events,

Ursula le Guin

but a place, a landscape of the imagination

which we can inhabit and return to.”

The words of Neil Philips reverberated around my head for some considerable time. “to explore the disjointed and troubled psychological and emotional landscape of the twentieth century through the symbolism of myth and folklore.” This was the landscape I had only too painfully come to know as a young adult, both the landscape of the novels of Alan Garner, but also “the troubled psychological and emotional landscape of the twentieth century.” At the age of just fifteen I had found myself contemplating thoughts of suicide, thoughts which left unchallenged and untreated continued to fester, with age ripening into a dark self-hatred, which at the age of twenty-six compelled me, in a desperate cry for help, to act upon those thoughts. One vigorous stomach pump and a good night’s sleep later I found myself at the mercy of the on-duty psychiatric team, who seemed to offer as much empathy and compassion as Caligula, and some time later I was cast out onto the streets with the vague promise of some follow up sessions with a psychotherapist, in about six months time, they said.

By some miracle of self-determination I fought my way through to my mid-thirties only to be faced with a further personal crisis of calamitous proportions, the consequences of which – a failed marriage, two estranged step-children, a flat-lining professional career, mounting personal debts – lay around me like the victims of a massacre. Something had gone wrong, horribly wrong. There were so many questions, but the materialist culture surrounding me, to a certain extent smothering me, seemed to hold no answers. The messages, both intentional and subliminal, seemed to be saying that my only purpose was to work to earn money to spend in cycles of the unrestrained satiation of morbid desires. I was lost. I needed a place of familiarity from which to assay what I had become. So it was that I returned to those books of my childhood: The Weirdstone of Brasingamen, The Moon of Gomrath, The Owl Service, Red Shift, in some vain attempt to find answers beyond the material.

So again I found myself on Alderley Edge, as I had on many, many occasions since that first encounter, many years ago. On this particular bleached winter’s morning, an oatmeal sun straining to peer over the tops of the birches, I headed out from the warmth of the Wizard Tea Rooms to retrace familiar steps around the three hundred acres of woodland now owned and managed by the National Trust.

No more than three hundred metres through the trees I arrived at Engine Vein, a section of open cast and collapsed mine that once was over twenty-five metres deep but was capped with concrete in 1979 for reasons of safety (the chasm into which my younger self gazed with such awe and wonder). A small iron door on the southern side of the cleft leads through a narrow passageway to the extensive chamber below, from where a labyrinth of drifts, levels and adits criss-cross and interconnect for mile upon mile. Back filled passages are still being discovered at Alderley, often by the Derbyshire Caving Club who have taken responsibility for the up keep of the mines under the direction of the National Trust, and who regularly hold open days for those wishing to take a subterranean exploration of these fascinating features[i].

The earliest evidence of mining at Alderley is to be found at Engine Vein and dates to the Bronze Age. The main ore extracted was copper, but cobalt, iron, lead, silver and even gold have also been found[ii]. In their book Prehistoric Cheshire, Victoria and Paul Morgan recount how an oak shovel found by 19thCentury miners in a section of mine at Brynlow to the south west of Engine Vein, has been radiocarbon dated to approximately 3,700 years old[iii]. A large number of stone hammer heads and similar tools were also discovered in material that had been used to backfill the open cast mine. The process of open cast mining at Engine Vein is believed to have involved the digging of small circular pits into the rock, the adjacent sides of which were then knocked though to expose the full length of the mineral vein. Evidence of this process can still be seen along the side of Engine Vein today, together with significant blackening of the rock, indicating the use fire setting to make the rock faces brittle in order to ease excavation.

From Engine Vein I headed to Beacon Lodge and crossed the Macclesfield Road. The hollows and depressions of the thick oak woodland still held the frost of the previous night as I made my way to lower ground and a clearing of sandy deposits. This was known as Sandhills, and is all that now remains at surface level of a considerable mining enterprise that took place during the 19thCentury. In 1857, James Mitchell obtained a twenty-year lease from Lord Stanley to extract ore in this location, initially using open cast excavation, which became known as West Mine. By 1860 the excavations were extended using tunnels into the rock both at West Mine and also at a new location in Windmill Wood, the no less imaginatively named Wood Mine. Between 1857 and 1863 the Alderley Edge Mining Company excavated an estimated 80,000 tons of ore producing 1,071 tons of copper metal with an estimated value of £84,132.[iv] Extraction of copper ore continued until 1878, by which time competition from overseas mining operations became too great, resulting in a global fall in the price of copper. The Alderley Edge Mining Company opted for voluntary liquidation and all mining activity ceased. At the beginning of the 20thCentury there were brief periods of renewed interest in ore extraction at Alderley, but again global economic forces resulted in very little profit for the prospectors and by 1919 the mines were once again abandoned. This heralded a darker era in the history of the mines and one that I must confess to having played a minor (not miner) role in, the problem of trespass. In 1929 two young Stockport men had wandered into West Mine and had become lost in the labyrinth of passageways, their torches eventually giving up, unable in the dark to find a way out. Their emaciated bodies were found in a side passageway three months later. Public concern at the fatalities did little to deter persistent trespassers. Between 1934 and 1937, forty-one people were fined by Wilmslow magistrates for offences of trespass in the mines[v]. In 1946 a man fell sixty-five feet to his death in ‘Plank Shaft’, again in West Mine, but the mine was not filled-in and fully sealed until 1960, the year The Weirdstone of Brisingamen was published.

“The widest shaft they had yet come upon lay before them, and stretched across its gaping mouth was a narrow plank.”[vi]

The ancient mines of Alderley claimed their last victim in 1974 when a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl fell thirty feet into Engine Vein, prompting the capping of the open cast shaft with concrete[vii]. In the fields and heathland to the north of Sandhills there is now no visible sign of West Mine or Wood Mine, although the lower levels are still accessible by means of two shafts dug in 1975 by the Derbyshire Caving Club, now kept firmly under lock and key.

Heading back through the woods further to the north, I arrived at the Macclesfield Road by a rusted early 20thCentury sign, now a protected monument, bearing the inscription “TO THE EDGE”. The sign pointed to Castle Rock, a beautiful outcrop of the Helsby and Wilmslow conglomerates and sandstones, from which the escarpments of the Alderley edge were hewn, which were laid down during the Triassic period of geology some 240 million years ago, in an arid environment prone to flash floods, which brought down debris from the surrounding mountainous areas, rich in mineral deposits[viii]. Despite the name, no evidence exists to suggest there was ever a castle on this site, however, evidence has been found of Neolithic implements and what the Morgan’s refer to as “an original Neolithic floor” of “friable brownish sandstone” and “loose bleached sand”, dating to around 5,000 years before present[ix]. Neolithic hunter-gatherers would no doubt have been attracted to the Edge because of the shelter it provided from the prevailing westerly winds and the plentiful supply of fresh water, the Edge being irrigated by at least three natural springs.

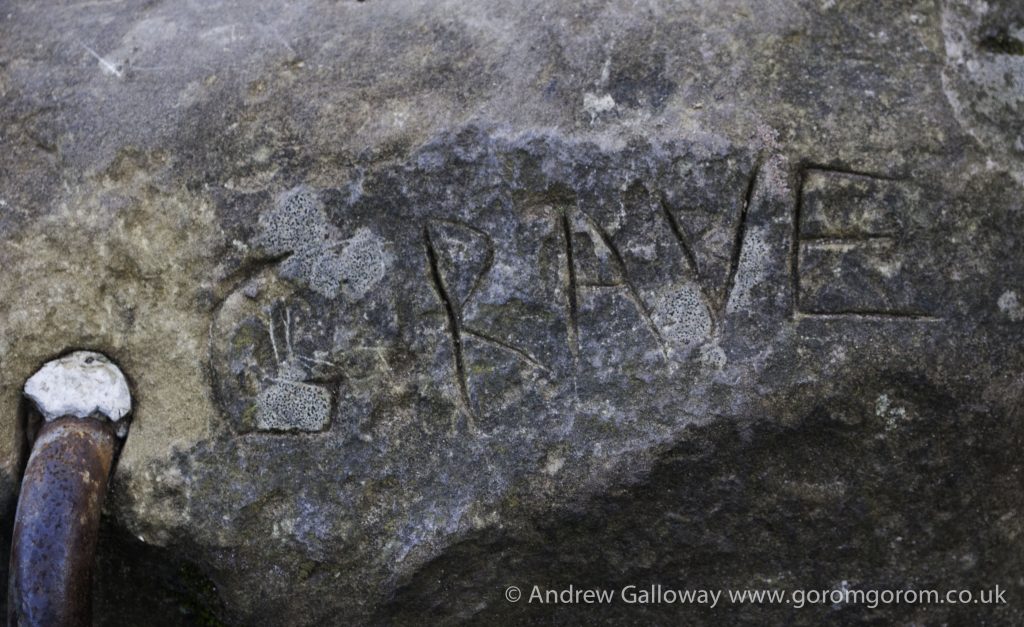

I climbed down under the face and ran my hands along the beautiful banding within the rock, tracing the ebb and flow of ancient sand dunes and river channels, tiny crystals of silica and mica coming away on my fingers. These exposures continued to the north, gradually sloping downwards towards the village, where one of the natural springs seeped from the foot of the cliff. Looking up I saw the face of a bearded man looking back at me – Wizard’s Well. This enigmatic carving is folly believed to have been carved into the rock by the great grandfather of Alan Garner, whose family lived in the area of the Hough below the Edge (pronounced huff)for over three hundred years. Although increasingly illegible, the letters read:

“Drink of this and take thy fill for the water falls by the Wizard’s will.”

Now faced with the suburban gardens of Mottram Road, I about turned, following the sculpted sandstone eastwards to where two further springs, known as Holy Well and Wishing Well, appeared each on either side of a buttress several metres in height. By the second well, the rock was dank, coated with a curtain of moss, dripping with water rich in minerals, from deep within the ground. I cupped my hands underneath the lush vegetation and let them fill with the crystal clear water, and drank.

Beyond the wellsprings, the ridge of Alderley Edge climbed to an eastern prospect over looking Glaze Hill. Here at Stormy Point an impressive crust of the Triassic conglomerate sat defiantly above the softer red mottled sandstones of the Wilmslow formation, bearing the scars of past mining activities. A long fissure in the conglomerate rock around fifty centimetres wide and up to two metres deep, topped by an unusual rectangular stone capping a circular hole, is known locally as the Devil’s Grave.

“If you run round theer three times widdershins Owd Nick’s supposed to come up and fetch you.”[x]

As children we would dare each other to take up the challenge and thus by encircling the stone in and anti-clockwise direction, would invoke the very devil himself. Of course we were always bitterly disappointed when having circumnavigated the offending monolith, nothing happened.

By early afternoon the Edge began to fill with the routine assault of families of over excited children, lolloping dogs and couples wearing matching Hunter wellington boots and Barbour jackets. Barley able to contain my resentment towards these interlopers, I quickly took the path through the fir trees behind the old Pilkington Family memorial and descended into the beautiful beech woodland of Saddlebole, where the path dropped steeply into a hollow, then through the beech trees to the break of slope.

Stories are important; the telling of stories more so. In his book The Philosopher and the Wolf, Mark Rowlands describes humans as “the animals that believe the stories they tell about themselves[xi],” and there is a very real part of myself, a part that perhaps a psychologist would refer to as the child ego state, which still wishes to believe in the legend of Alderley. And although it may be my inner child who turns up the undergrowth in the nooks and dingles of Alderley wood in search of ….what? something, some recognition, some identification, this desire is by no means childish. It is the desire that has driven the creation of myth and the telling of stories since humans first acquired the ability of speech.

At Ridgeway Wood I came across a small waterfall, which tumbled over loose shale into a deep ravine. In late November of 1745, rumour spread amongst the families of the Hough that a Jacobite army loyal to the ‘Young Pretender’, Prince Charles Edward Stuart were heading south from the undefended city of Manchester to Derby, their route taking them via Alderley. The alarmed inhabitants took their beds, blankets and family heirlooms and hid out in the ravine until the ill-fated rebellion had past by.

From above the wood I returned north towards an earthen mound topped by a memorial stone. Marking the highest ground, this was the site of an Armada Beacon built around 1577 as part of an Elizabethan early warning system comprising a chain of fire signals strategically located on high ground, stretching from the south coast of England, to London and onwards throughout the country. The original building was a simple construction of four walls around a fire basket or pot, within which wood, pitch and tar were to be lit should the need arise, as it did in 1588 when the Spanish fleet attacked the English coast[xii]. Lord Stanley, owner of the Alderley estate during the 17thCentury, arranged for the beacon to be re-built as part of landscaping works, with higher walls and a pitched roof. This building collapsed during a storm in 1931, the remains of which lay scattered around the site and were used to build the current memorial stone.[xiii]

The earth mound upon which the beacon stood has been scheduled as a Bronze Age barrow, a type of prehistoric burial site also found at Seven Firs just to the south of Engine Vein and in Brynlow wood, nearby[xiv]. It is not inconceivable that the association of the legend of the sleeping knights with Alderley Edge lies in the presence of these barrows, possibly the burials of Bronze Age chieftains. Alderley was certainly of great importance to Bronze Age people because of the mineral wealth held within the earth. As the Bronze Age passed into the Iron Age, the ceremonial rights and traditions of the former people would have been forsaken, remembered only as stories and passed from generation to generation by oral tradition.

Through the thickness of trees: fir, pine, oak, ash and birch, I could hear them shouting after me, calling my name. Adult voices, distant and dislocated from the hypnotic draw of the open wound in the Cheshire woodland. I believed I had found the fabled Iron Gates deep within the tactile rocks of Alderley Edge and was intent on discovering the whereabouts of the elusive Wizard. Unbeknown to the child, the wizard in question was not Ambrosius, or Merlin, or Cadelin, but Alan Garner himself. For undoubtedly a spell had been cast over me, one from which I would never recover, and what in fact I had discovered was not the mythic Iron Gates, but something far more precious. Precious to the child, even more precious to the man as he now found himself, stumbling around in the mid-life forests and spiritual vacuity of twenty-first century Britain, desperately searching for some vestige of meaning.

[i]Derbyshire Caving Club www.derbyscc.org.uk

[ii]Chris J. Carlon, The Alderley Edge Mines, 1979, John Sherratt & Son Ltd, pg29

[iii]Victoria & Paul Morgan, Prehistoric Cheshire, Landmark Publishing Ltd. 2004, pg71

[iv]Carlon, Chris, J. The Alderley Edge Mines, John Sherratt and Son Ltd, 1979, pg 52 and 66.

[v]Ibid. pg122

[vi]Alan Garner, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, Op. cit. pg127

[vii]Carlon, Chris, J. The Alderley Edge Mines, Op. cit. pg124

[viii]The nomenclature of the Upper Triassic sequence was changed during the 1980’s. What had originally been referred to as the Bunter and Keuper Sandstones, became incorporated into the Sherwood Sandstone Group. The two main stratigraphic sequences visible at Castle Rock, Alderley Edge are the Upper Mottled Sandstone (formerly part of the Bunter sequence), above which is the Engine Vein Conglomerate (formerly part of the Keuper sequence). See Benton, M.J., Cook, E. & Turner, P. (2002) Permian and Triassic Red Beds and the Penarth Group of Great Britain, Geological Conservation Review Series, No. 24, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, 337 pp.

[ix]Victoria & Paul MorganPrehistoric Cheshire, Op. cit. pg33.

[x]Alan Garner, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, Op. cit. pg33

[xi]Rowlands, Mark. The Philosopher and the Wolf, Granta Publications, 2008, pg2

[xii]Stanley, L. Alderley Edge and its neighbourhood, Op. cit.

[xiii]Ron Lee, Portrait of Wilmslow, Hanforth & Alderley Edge, 1996, Sigma Press, Wilmslow, pg72.

[xiv]Victoria & Paul MorganPrehistoric Cheshire, Op. cit. pg119

A brave telling, thank you.